Pakistani military as the world’s fifth largest force and a nuclear power to boot, ought to be a monolithic institution of high discipline and professionalism that flexes its powerful where- withal with due care and consid- eration.

For a nation where the mili- tary has wielded unlimited and uninterrupted power since inde- pendence, either officially (under military rulers like Ayub Khan, Yahya Khan, Zia-ul-Haq or Per- vez Musharraf) or under the pre- text of a civilian government (like now) ~ the unity and stability of this institution is paramount, especially when society, civilian politicians and the clergy have shown recklessly violent and implosive tendencies within.

Politicisation and the ac- companying rot started early with the selection of the first ‘native’ Commander-in-Chief, General Ayub Khan.

Ayub’s name did not even figure in the initial panel that was put forward for consideration owing to professional and senior- ity concerns. Ayub, as a Major General then became the junior most in the list, after his name was forcibly included by Defence Secretary, Iskandar Mizra. Even though Ayub had superseded fel- low-officers, the institution sur- vived that contentious decision and almost accepted such-like supersessions as a matter of rou- tine. Prior to the elevation of the current Pakistani Chief, Asim Munir, only four of the prior fourteen, had been made Chief as per seniority ~ General Asim Munir is also believed to have been forcibly included in the list as his name was not initially pro- posed as he was to retire two days before the retirement of the then incumbent, Gen Qamar Bajwa. Yet the institution or ‘establishment’ (as it is colloqui- ally called in the Pakistani narra- tive) has accepted competitive wrangling for the top post as no threat to stability.

Importantly, Ayub was to set another infamous precedent that was to be assiduously followed by successive chiefs who were brought into the chair by political manipulations, only to bite the hand that was responsible for giving them the top job in the first place. Ayub had dutifully exiled Iskandar Mirza (who had become the President) ~ just as later General Zia-ul-Haq sent his one-time mentor and selector, Zulfiquar Bhutto to the gallows, and just as General Pervez Musharraf had exiled Nawaz Sharif (both Zia and Musharraf had been selected for their ‘safe’ Mohajir origins in a Punjabi-Pathan dominated Army).

However, the Pakistani Army has had brewing discom-fiture within its ranks that did lead to some internal strife and the first recorded one was as early as 1951 when Maj Gen Akbar Khan (Rawal-pindi Conspiracy) conspired against the govern- ment of Liaquat Ali Khan un- successfully. In 1980, fissures within the ‘establishment’ led Maj Gen Tajammul Hussain Ma- lik to attempt assassinating Zia- ul-Haq, again unsuccessfully. However, despite these two major incidents, irrespective of the tensions and dislikes within the ‘establishment’ ~ the insti- tution supported and offered ‘cover fire’ to many of the dis- graced military leaders, post their removal from national leadership e.g., Gen Yahya Khan, Tikka Khan, Pervez Musharraf etc.

Occasional ‘purges’ of those harbouring extremist religious views or corruption taints were not opposed, not even from within. One important anchor- age that helped the ‘establish- ment’ to remain by and large united was the lack of partisan/ideological colour in the institution (odd cases of the likes of Lt Gen Hamid Gul, notwith- standing), and the fact that post- retirement largesse and rehabili- tation of senior ranks ensured a financially privileged standing in the society, with institutional unity being an invaluable collat- eral necessity.

This institutional stability is particularly important given that Pakistan hosts up to 120 nuclear warheads and it concurrently practices terrorism as a state pol- icy (even though it is not official- ly stated). Now, given the process

of natural seepage and affliction of the larger societal sensibilities and regressions onto a sub-institution within its midst i.e. the Pakistani military ~ it is absolutely critical that the safety of the nuclear pro- gramme is never compromised. For long, fears of Pakistani nuclear wherewithal fal- ling into wrong or roguish hands has haunted security mandarins across the globe. It is not an unfounded fear for some time ago, there were credible reports of mass desertions in three infantry brigades at Par- achinar, Kohat and Turbat.

These brigades were battling the extremist elements in the restive northern areas along the Durand Lines ~ a sense of frater- nal emotions were said to be be- hind the dissonance.

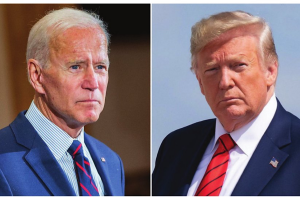

To assume that all amongst the vast ecosystem and network of the Pakistani nuclear pro- gramme would remain oblivious to the societal preferences, mor- ass and extremism is wishful thinking. US President Joe Biden had famously described Pakistan, “as one of the most dangerous nations in the world” with “nuclear weapons without any cohesion”!

Very recently, the sudden (though not wholly unexpected) resignation of the former Direc- tor General of Inter Services In- telligence (ISI), Lt Gen Faiz Ham- eed, along with the co-timed rescinding of ceasefire and sud-den escalation of religio-terror attacks by Tehrik-e-Taliban Pak- istan (TTP), has security experts worried about the deep politici- sation (Faiz Hameed’s bonhomie with the Taliban and the previ- ous Imran Khan dispensation) within the senior ranks of the ‘establishment’. This is not a reassuring picture of unity and stability.

Already counteraccusations are flying with politicians openly alluding to many senior Pakistani military men who were in favour of resettling and rehabilitating the 20000-30000 odd TTP fight- ers, back on Pakistani soil.

With this governance back- drop and unhinged maneuvering besetting the developments in Pakistan, it is not unfathomable to imagine a specter of a ‘dirty bomb’ or compromises to vari- ous levels of security afforded on Pakistan nuclear infrastructure. Not long back, issues of reckless and surreptitious proliferation under the AQ Khan tenure had surfaced.

Too many coincidences link- ed to various security personnel and escalation of violence have yet again reignited the question of security. The entirety of Pak- istani society is seemingly mired in a dangerous admixture of reli- gious puritanism, partisanship, sectarianism and insurgency movements, the impact of which on an institution such as the Pak- istani military or ‘establishment’, cannot be discounted. Radical elements within the ‘establish- ment’ are the biggest threat and the curious case of AQ Khan (though not strictly a part of the ‘establishment’) highlights the practical dangers.

More likely than a launch of a full-fledged nuke, crude radio- logical terrorism (with radioac- tive material falling in wrong hands through deliberate com- plicity or even theft) cannot be ruled out. With the crumbling and disintegration of various arms of Pakistani governance in sheer desperation as socio-eco- nomic stability melts, this insti- tutional rot is fraught with incal- culable dangers.

(The writer is Lt Gen PVSM, AVSM (Retd), And former Lt Governor of Andaman Nicobar Islands and Puducherry)